- Three Curious Things

- Posts

- Half a logo, dystopian parks, surveillance mirrors

Half a logo, dystopian parks, surveillance mirrors

When art stops being something you watch and becomes something you feel

Most of us scroll past hundreds of headlines about climate change, surveillance, and inequality every week. We know these problems exist. Abstractly, distantly, like facts we've memorized but never felt. The challenge for artists and activists isn't getting information out there; it's making people actually feel something about it. This week, three projects that refuse to let you stay comfortable in the audience. They pull you onto the stage, into the experience, making you participant instead of observer.

Whether it's drawing your own protest sign, watching your face get tagged by fake surveillance, or paying admission to a theme park designed to make you miserable, these projects understand something crucial: we process the world differently when we're inside it rather than looking at it.

1. The logo that won't exist without you.

Sun Day's logo is deliberately incomplete. Half a sun with blank space where you're supposed to draw the rest. It's a clever inversion of typical climate activism branding, which usually features finished, polished imagery of melting ice caps or sad polar bears. Instead, environmentalist Bill McKibben and design studio Collins created something that requires participation before it even exists. The message is straightforward: we have half of what we need (the technology for clean energy), now finish the job (by demanding political action).

Collins wanted it to look homemade rather than professionally polished, because "when really well-meaning designers get involved, they end up looking like national design conferences instead of something where people make shit." It's a recognition that climate activism needs to feel like a movement, not a brand campaign. The half-sun becomes both protest sign and permission slip. An invitation to add your voice rather than just repost someone else's. Where Earth Day had that iconic Apollo 8 photograph of our fragile blue marble, Sun Day offers something less perfect but potentially more powerful: a logo that doesn't exist until you help create it.

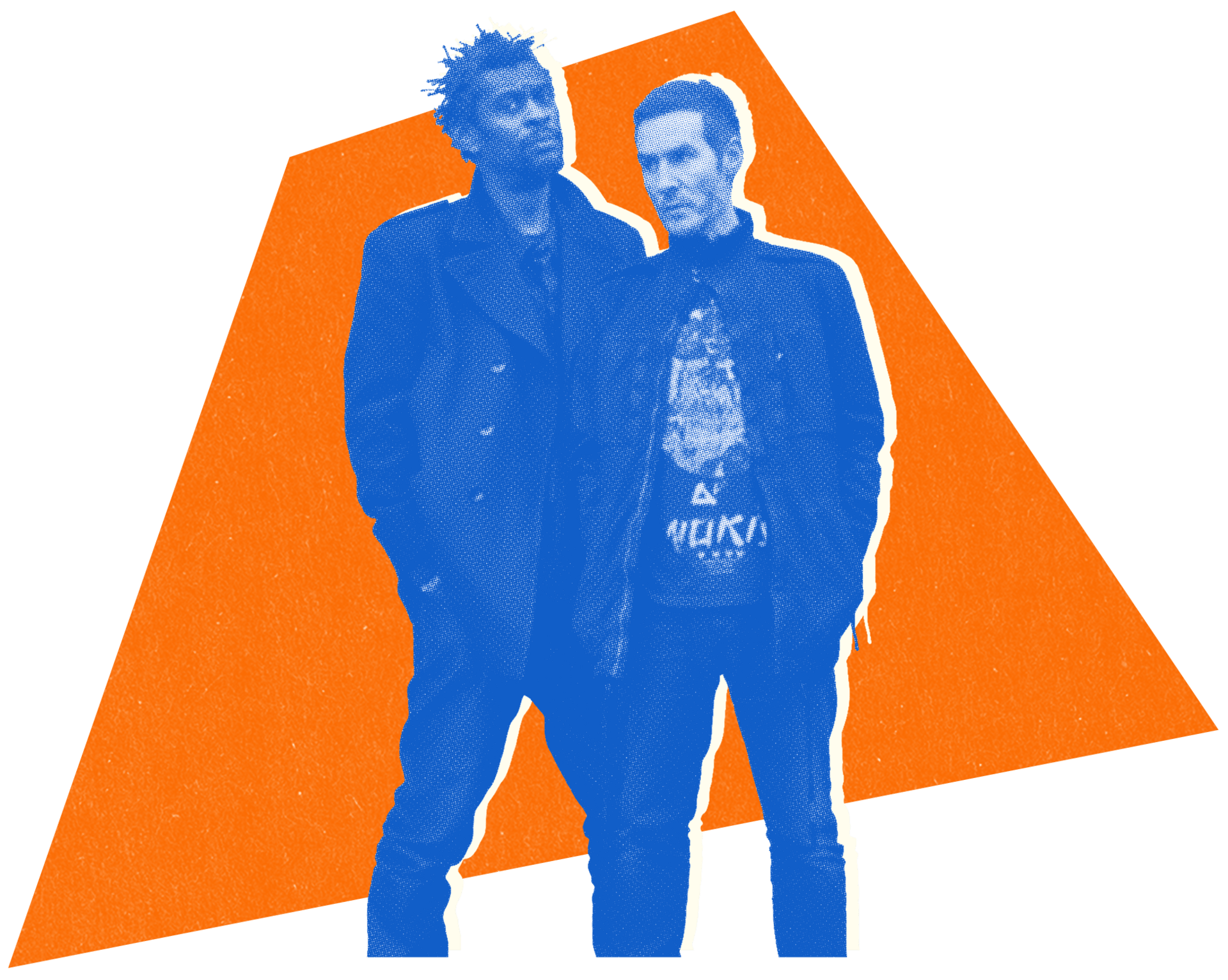

2. The show that watched you back.

We all know companies are tracking us. Our searches, our locations, our shopping habits, our faces. But knowing it abstractly and feeling it are different things. Massive Attack turned their concerts into a visceral experience of surveillance, projecting fake facial recognition screens that appeared to tag audience members in real-time with labels like "student protester". Standing in a crowd watching yourself get categorized by an algorithm makes the abstract suddenly personal. It's one thing to read about data collection in a privacy policy you'll never finish; it's another to see your face on a screen being assigned a fictional profile you didn't consent to.

Most activism about surveillance lives in articles, tweets, or documentaries - media you can scroll past or ignore. But when you're at a show, surrounded by people, all of you being "watched" together, the experience becomes immediate and shared. Massive Attack took something intangible (that creeping feeling that we're all being monitored) and made it something you could see and feel in real-time. It's experiential activism that doesn't lecture; it just shows you what's already happening, using art to make the invisible visible. The fact that some outlets thought it was real surveillance only proves how normalized this has become.

3. The unhappiest place on earth.

Remember the last time you stood in line at a theme park, paying too much money to be herded through crowds? In 2015, Banksy flipped that script entirely with "Dismaland"—a dystopian theme park where security guards were hostile, rides were broken, and the whole experience was designed to make you uncomfortable. Visitors paid admission to be insulted during pat-downs, watch Cinderella's carriage crash with paparazzi figurines swarming the wreckage, and confront installations about refugees, inequality, and capitalism. It was Disney's nightmare mirror, replacing manufactured happiness with pointed social commentary.

We know how theme parks are supposed to work: they sell escapism, optimism, and carefully controlled fun. By inverting that formula with surly staff and depressing attractions, Banksy created an experience that made political issues visceral rather than abstract. You weren't just reading about immigration crises or income inequality, you were standing in a miserable park in the rain, surrounded by art that refused to let you look away. Sometimes the best way to make people think about uncomfortable truths isn't through lectures or statistics, but by building a terrible theme park and watching them pay to feel bad about the world.

Found something curious? Or maybe you want to be a guest curator for one of the next issues? Simply hit ↩️ reply.

Reply